The ripening of bananas is a fascinating natural process governed by the release of ethylene gas, a plant hormone that triggers a cascade of biochemical changes. While most consumers only see the final stages of ripening—when the fruit turns from green to yellow—the underlying mechanisms involve multiple phases, each with distinct physiological and chemical transformations. Understanding these stages is crucial for both commercial suppliers aiming to optimize shelf life and home consumers seeking to manage their fruit's ripeness.

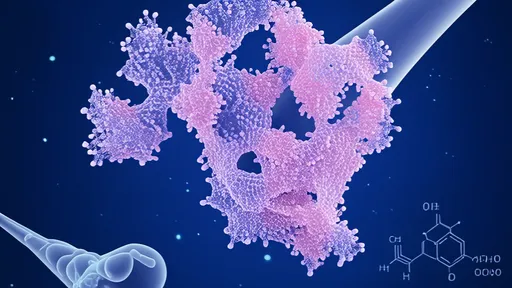

Bananas begin their journey as hard, green fruits with high starch content and minimal sweetness. At this pre-climacteric stage, ethylene production is minimal, and the fruit remains resistant to softening. However, once harvested, bananas enter the climacteric phase, marked by a dramatic surge in ethylene synthesis. This gaseous hormone acts as a signaling molecule, initiating a series of metabolic reactions that break down complex carbohydrates into simple sugars, soften cell walls, and alter pigmentation.

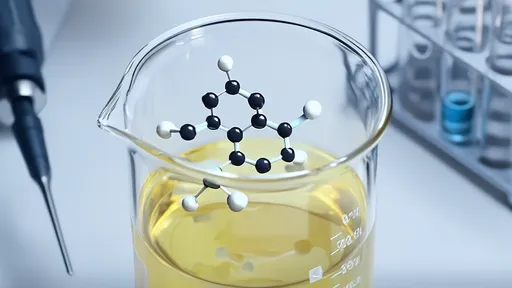

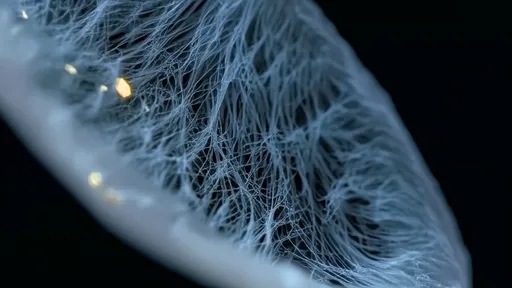

The initial ethylene burst is often imperceptible to the naked eye but sets the stage for visible changes. As internal ethylene concentrations rise, the fruit's respiration rate spikes, consuming oxygen and releasing carbon dioxide at an accelerated pace. This metabolic shift generates the energy required for enzymatic activity, particularly amylases and pectinases, which target starches and pectins respectively. The breakdown of these compounds transforms the banana's texture and flavor profile, turning it from starchy and astringent to soft and sweet.

Interestingly, ethylene release follows an autocatalytic pattern—the gas stimulates its own production, creating a feedback loop that accelerates ripening. This explains why bananas seem to ripen suddenly after a period of apparent stability. Commercial producers exploit this phenomenon by exposing green bananas to exogenous ethylene in controlled environments, synchronizing the ripening process across entire shipments before distribution.

As the peel transitions from green to yellow, chlorophyll degradation becomes evident while hidden carotenoid pigments emerge. Simultaneously, volatile aromatic compounds like isoamyl acetate (responsible for the classic banana scent) develop, peaking when the fruit reaches optimal edibility. The peel's color change isn't merely cosmetic—it correlates with biochemical readiness. A study published in Postharvest Biology and Technology found that bananas with fully yellow peels exhibit up to 20% higher sugar content than their partially green counterparts.

The final stages of ethylene production coincide with the fruit's most vulnerable period. As sugars accumulate and cell walls continue weakening, the banana becomes prone to mechanical damage and microbial invasion. Brown spots appear as polyphenol oxidase enzymes react with oxygen, a visual indicator that the fruit has entered the senescence phase. While some consumers prefer bananas at this stage for their intensified sweetness, others may find the texture overly soft.

Temperature plays a critical moderating role throughout this process. Storage at 13-15°C (55-59°F) can extend the pre-climacteric phase by slowing ethylene sensitivity, while warmer environments hasten ripening. This explains why refrigerating bananas (typically below 12°C) disrupts cellular membranes, causing premature darkening despite actually inhibiting ethylene activity—a counterintuitive outcome that puzzles many home storage attempts.

Modern supply chains have developed sophisticated protocols to manage ethylene exposure. Modified atmosphere packaging with ethylene absorbers, timed ethylene gas applications in ripening rooms, and precision temperature controls allow distributors to deliver bananas at targeted ripeness levels. Meanwhile, researchers continue exploring ethylene-inhibiting technologies, including nanoparticle films and genetic modifications to delay ripening without compromising quality.

For consumers, recognizing ethylene's role suggests practical strategies. Separating bananas from other ethylene-sensitive produce (like apples or avocados) can prevent accelerated ripening, while wrapping stem ends reduces ethylene emission points. Some tropical communities still use traditional methods—hanging bunches in shaded, well-ventilated areas—which naturally regulates temperature and ethylene dispersion better than countertop storage.

The study of banana ripening extends beyond culinary applications. NASA has investigated ethylene control for plant growth in space missions, while medical researchers examine ethylene precursors for potential connections to human hormone metabolism. As climate change alters growing conditions and supply chain pressures intensify, understanding ethylene's precise mechanisms becomes increasingly valuable for food security and waste reduction initiatives worldwide.

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025