The world of citrus essential oils is a fascinating realm where science meets nature's intricate design. Among the most captivating aspects of citrus fruits lies within their peel – specifically, the oil glands or vesicles that harbor these precious aromatic compounds. These microscopic structures hold the key to understanding how citrus fruits produce, store, and release their characteristic fragrances and flavors.

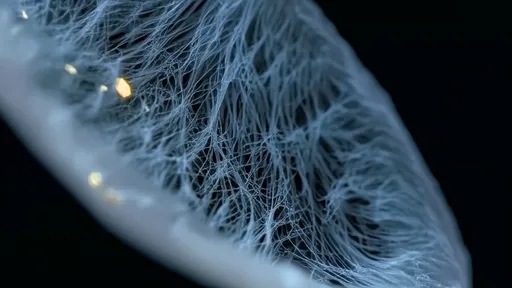

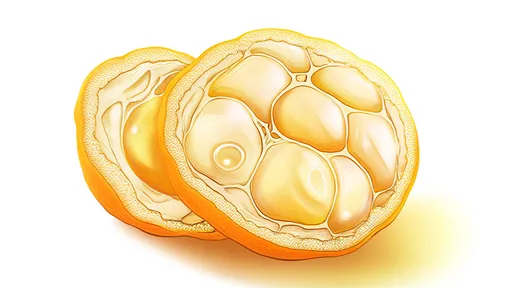

Under the microscope, citrus peel reveals a stunning architectural marvel. The outer layer, or flavedo, appears dotted with countless tiny sacs that glisten like miniature chandeliers when illuminated. These are the oil vesicles – nature's perfectly engineered containers for essential oils. Their distribution pattern varies across different citrus species, creating unique aromatic profiles that distinguish a lemon from an orange or a grapefruit.

The formation of these oil vesicles begins during the fruit's early developmental stages. As the citrus fruit grows, specialized cells in the peel start to differentiate into oil-producing structures. What begins as a small cluster of cells gradually transforms into a spherical sac filled with volatile compounds. The process resembles a carefully choreographed dance of cellular differentiation, where each step follows precise biochemical cues to create these aromatic reservoirs.

Advanced microscopic techniques have allowed researchers to observe these structures in unprecedented detail. Scanning electron microscopy reveals the three-dimensional architecture of the oil glands, showing how they protrude from the peel's surface like tiny domes. Transmission electron microscopy provides even deeper insight, exposing the intracellular machinery responsible for synthesizing and accumulating essential oil components.

What makes these microscopic observations particularly remarkable is how they correlate with sensory experience. When you zest a lemon or squeeze an orange peel, the bursting of these fragile sacs releases a spray of essential oil that carries the fruit's signature aroma. The size, density, and structural integrity of these vesicles directly influence how intensely and how quickly these aromas are released when the peel is disturbed.

Seasonal variations and growing conditions leave their mark on these microscopic structures. Citrus fruits harvested in cooler climates often develop thicker peels with more densely packed oil vesicles compared to their warm-climate counterparts. The vesicles themselves may appear more robust, with thicker walls that better protect the volatile oils from environmental degradation. These subtle differences explain why the same citrus variety can produce essential oils with slightly varying aromatic profiles depending on its origin.

The distribution pattern of oil vesicles isn't uniform across the entire fruit surface. Microscopic surveys have shown that their density tends to be highest near the stem end and decreases toward the blossom end. This gradient distribution might relate to the fruit's vascular system, which transports the precursors needed for oil biosynthesis. The equatorial region of the fruit often shows an intermediate vesicle density, creating a unique topographic map of aromatic potential across the peel's surface.

Modern imaging technologies have revealed surprising details about vesicle development. Time-lapse microscopy studies show that new oil vesicles continue to form throughout the fruit's growth period, though the rate slows as the fruit approaches maturity. This ongoing vesicle formation ensures that even as older sacs rupture or degrade, new ones take their place to maintain the peel's aromatic capacity.

Comparative studies across citrus varieties reveal fascinating differences in vesicle architecture. Mandarin peels, for instance, tend to have smaller but more numerous oil vesicles compared to thick-peeled varieties like pomelos. These structural variations directly impact extraction methods – mandarin oil requires gentler handling to avoid crushing the delicate vesicles, while pomelo peels can withstand more vigorous processing.

The cellular environment surrounding these oil vesicles is equally intriguing. Microscopic observations show that each vesicle exists in a carefully maintained microenvironment. Specialized parenchyma cells surround the oil sacs, possibly serving protective or regulatory functions. Some researchers suggest these neighboring cells might control water balance or provide biochemical precursors for oil synthesis, though the exact mechanisms remain under investigation.

Climate change research has brought new urgency to studying these microscopic structures. As temperatures rise and weather patterns shift, citrus growers need to understand how these changes might affect oil vesicle development. Preliminary studies suggest that prolonged heat stress can lead to thinner vesicle walls and higher oil volatility, potentially altering both the yield and quality of extracted essential oils.

From a commercial perspective, microscopic analysis of oil vesicles has become an invaluable quality control tool. By examining vesicle density and integrity, producers can predict essential oil yields and identify optimal harvest times. Some forward-thinking distilleries now use microscopic imaging as part of their standard quality assessment, recognizing that the secrets to premium citrus oils lie in these minuscule structures.

The therapeutic properties of citrus essential oils find their origin in these microscopic vesicles. Each tiny sac contains a complex mixture of terpenes, aldehydes, esters, and other bioactive compounds. The precise composition varies not just between species, but even among individual vesicles within the same fruit. This chemical diversity, visible only at the microscopic level, explains why whole citrus oils often have broader therapeutic applications than their isolated components.

As research techniques advance, scientists are uncovering even more sophisticated aspects of vesicle biology. Fluorescence microscopy has revealed that some vesicles appear to specialize in particular compounds – certain sacs might concentrate limonene while others accumulate more linalool or citral. This compartmentalization at the microscopic level could explain how citrus fruits maintain such complex and balanced aromatic profiles.

The study of citrus oil vesicles has implications beyond aromatherapy and flavoring. Pharmaceutical researchers are particularly interested in how these natural micro-containers protect and stabilize their volatile contents. Understanding these mechanisms could lead to breakthroughs in drug delivery systems, inspiring new ways to package and protect sensitive medicinal compounds.

Perhaps most remarkably, these microscopic observations connect us to centuries of citrus cultivation. When Renaissance perfumers rubbed citrus peels between their fingers to release the fragrant oils, they were unknowingly bursting these same microscopic vesicles that modern scientists now study with electron microscopes. This continuity between traditional knowledge and cutting-edge science underscores the enduring fascination with citrus essential oils and their microscopic origins.

Looking ahead, researchers anticipate that studying citrus oil vesicles will yield even more surprises. New imaging technologies may reveal how these structures interact with the fruit's microbiome or respond to environmental stressors at the cellular level. Each advance in microscopic resolution brings us closer to fully understanding these remarkable natural oil reservoirs and their role in citrus biology.

The humble citrus peel, when viewed through the lens of modern microscopy, transforms into a landscape of wonder. Each oil vesicle represents nature's solution to storing volatile aromas – a solution refined over millions of years of citrus evolution. As we continue to explore these microscopic worlds, we gain not just scientific knowledge, but a deeper appreciation for the complexity hidden within everyday fruits.

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025