The culinary world has long been fascinated by the transformative power of heat on animal connective tissues, particularly when it comes to the conversion of collagen into gelatin. Among these tissues, beef tendon stands out as a remarkable case study due to its dense collagen structure and the dramatic textural changes it undergoes during prolonged cooking. This article explores the gelatin formation curve of beef tendon during braising, examining the complex interplay of time, temperature, and molecular breakdown that creates that coveted unctuous mouthfeel in dishes ranging from pho to Taiwanese beef noodle soup.

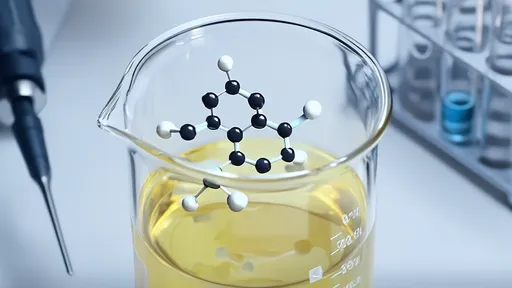

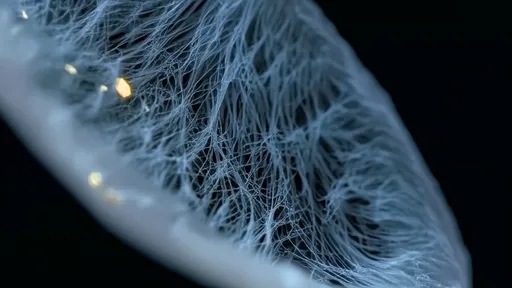

Understanding the collagen matrix in beef tendon requires us to first appreciate its biological function. Tendons serve as tough, fibrous connectors between muscles and bones, composed primarily of type I collagen arranged in tightly packed parallel bundles. This structural protein accounts for about 85% of the tendon's dry weight, with the remaining components being elastin and proteoglycans. The collagen molecules themselves are triple helices of polypeptide chains rich in glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline, forming incredibly strong fibrils that resist most mechanical stresses - until heat and moisture enter the equation.

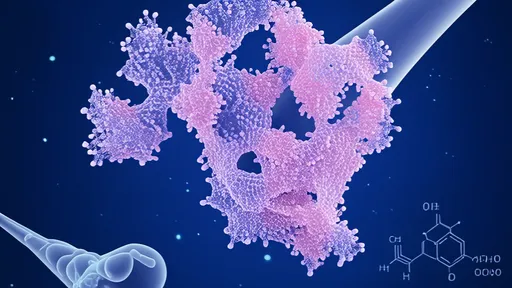

When subjected to moist heat cooking methods like braising or stewing, the collagen undergoes a process called thermal denaturation. Initially, the hydrogen bonds stabilizing the triple helix structure begin to break at temperatures around 60-70°C (140-158°F). However, the covalent cross-links between collagen molecules maintain the overall structure until higher temperatures are reached. This explains why quick cooking methods fail to tenderize tough cuts - the transformation requires both sufficient heat and time to allow the gradual unwinding of these stubborn molecular bonds.

The gelatinization process follows a distinct sigmoidal curve when plotted against time at constant temperature. During the initial phase, little visible change occurs as heat penetrates the tissue and begins disrupting the weaker bonds. This lag period can last anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours depending on the size of the tendon pieces and the cooking temperature. Food scientists refer to this as the "activation energy" phase where sufficient thermal energy must accumulate to initiate the major structural changes.

As the process continues, the curve enters its steepest slope where the majority of collagen converts to gelatin. This is when the tendon undergoes its most dramatic textural metamorphosis - from rubbery and tough to tender with that characteristic gelatinous quality. The rate of conversion depends heavily on temperature; at 90°C (194°F), complete conversion might take 4-6 hours, while at 100°C (212°F) it may occur in 2-3 hours. Interestingly, going beyond 100°C doesn't significantly accelerate the process, as the limiting factor becomes the diffusion rate of water molecules into the tissue rather than just thermal energy.

Several factors influence the gelatin formation curve beyond just time and temperature. The age of the animal plays a crucial role - tendons from older cattle contain more mature collagen with additional cross-links, requiring longer cooking times. Acidic environments (like those created by adding tomatoes or wine to a braise) can accelerate the process by helping hydrolyze collagen, while alkaline conditions tend to slow it down. The physical size of the tendon pieces also matters tremendously; halving the thickness of tendon slices can reduce required cooking time by more than 30% due to increased surface area for heat penetration.

The final phase of the curve shows diminishing returns, where additional cooking time yields progressively less gelatin formation. At this point, most accessible collagen has already converted, and continuing to cook primarily serves to break down the gelatin molecules themselves into smaller peptides. This can lead to a loss of that desirable viscous quality in the cooking liquid, demonstrating that there is indeed an optimal endpoint for gelatin extraction. Professional chefs often judge this by feel - the perfect tendon should offer slight resistance when pierced but still hold together, indicating substantial but not complete collagen conversion.

Modern culinary techniques have begun mapping these gelatinization curves with scientific precision. Sous vide cooking, with its precise temperature control, allows chefs to target specific points on the curve for different textural effects. At 72°C (162°F) for 48 hours, beef tendon achieves a unique texture that's tender yet still retains some bite, while traditional boiling methods that reach higher temperatures faster produce the more familiar fall-apart consistency. These controlled experiments have revealed that the gelatinization process isn't a simple linear progression, but rather occurs in waves as different types of collagen cross-links break at different energy thresholds.

The implications of understanding this gelatin formation curve extend beyond just beef tendon. Similar principles apply to other collagen-rich ingredients like pork skin, oxtail, or chicken feet, each with their own unique conversion characteristics based on collagen type and structure. This knowledge empowers cooks to make informed decisions about cooking times and methods based on their desired textural outcomes, whether they're aiming for a clear consomme with delicate viscosity or a rich, unctuous stew with substantial mouthfeel.

As research continues, we're discovering even more nuances about this fundamental culinary transformation. Recent studies suggest that resting periods during cooking - alternating between heating and cooling phases - may enhance gelatin extraction by allowing partial reformation of bonds that then break more completely during subsequent heating. Other investigations explore how different breeds of cattle or feeding regimens affect the collagen structure in tendons, leading to variations in their gelatinization curves. This ongoing exploration reminds us that even the most traditional cooking processes contain layers of complexity waiting to be uncovered.

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025